…You have to have a heart. This ties into my anthropology background. We’re taught as anthropologists to remove our biases, at least the ones we’re aware of. You can’t remove the implicit ones, but you can work on the ones you’re aware of. When doing work like this, you have to remove what you think is right and be able to listen objectively to people that society might deem as on the fringes or not ideal citizens. When you listen with an open and objective heart, you can find the humanity in people and see them for who they are…

I had the pleasure of talking with Kelley Kali. Kelley Kali, born Kelley Kali Chatman in Northridge, California, has emerged as a significant voice in the world of independent filmmaking. With a unique background in anthropology and cinematic arts, she has consistently focused on telling stories from marginalized communities, using her platform to shed light on critical social issues.

Kali grew up in the culturally diverse San Fernando Valley in Southern California, the daughter of an African-American pastor from Alabama and an Irish-German aerospace engineer from Pittsburgh. This blend of Southern, East Coast, and multicultural influences shaped her worldview, fostering an appreciation for diverse perspectives and a passion for storytelling. Reflecting on her upbringing, she notes, “I grew up in a house of pure juxtaposition,” a theme that permeates her work.

Kali pursued her undergraduate studies at Howard University, where she majored in anthropology with a focus on archaeology and minored in film and classical civilization. Her interest in storytelling took root during this period, influenced by her father’s pastoral narratives and her own curiosity about human cultures and histories. After her time at Howard, she directed multiple episodes of the Belizean dramatic television series “Noh Matta Wat!”

Further honing her craft, Kali earned a Master of Fine Arts from the USC School of Cinematic Arts in TV and Film Production. Her short film, “Lalo’s House,” which tackled the issue of child sex trafficking in Haiti, served as her thesis project and won the 45th Student Academy Award and was in consideration for the 91st Academy Awards. .

Kelley Kali’s career has been marked by a commitment to impactful storytelling. Her debut feature film, “I’m Fine (Thanks for Asking),” released in 2021, is a testament to her resourcefulness and dedication. Shot during the COVID-19 pandemic, the film was funded initially with her stimulus check and unemployment benefits. Despite these financial constraints, it went on to win the Special Jury Award at South by Southwest (SXSW), highlighting Kali as a multi-hyphenate filmmaker and her ability to deliver powerful narratives under challenging circumstances.

In 2022 , Kali directed “Jagged Mind,” an LGBTQ+ psychological time-loop thriller featuring Maisie Richardson-Sellers. Set in Little Haiti, Miami, the film weaves Afro-Caribbean cultural elements into its narrative, reflecting Kali’s dedication to authentic representation. “Jagged Mind” premiered at the American Black Film Festival, further cementing her reputation as a director capable of blending diverse cultural elements into compelling stories.

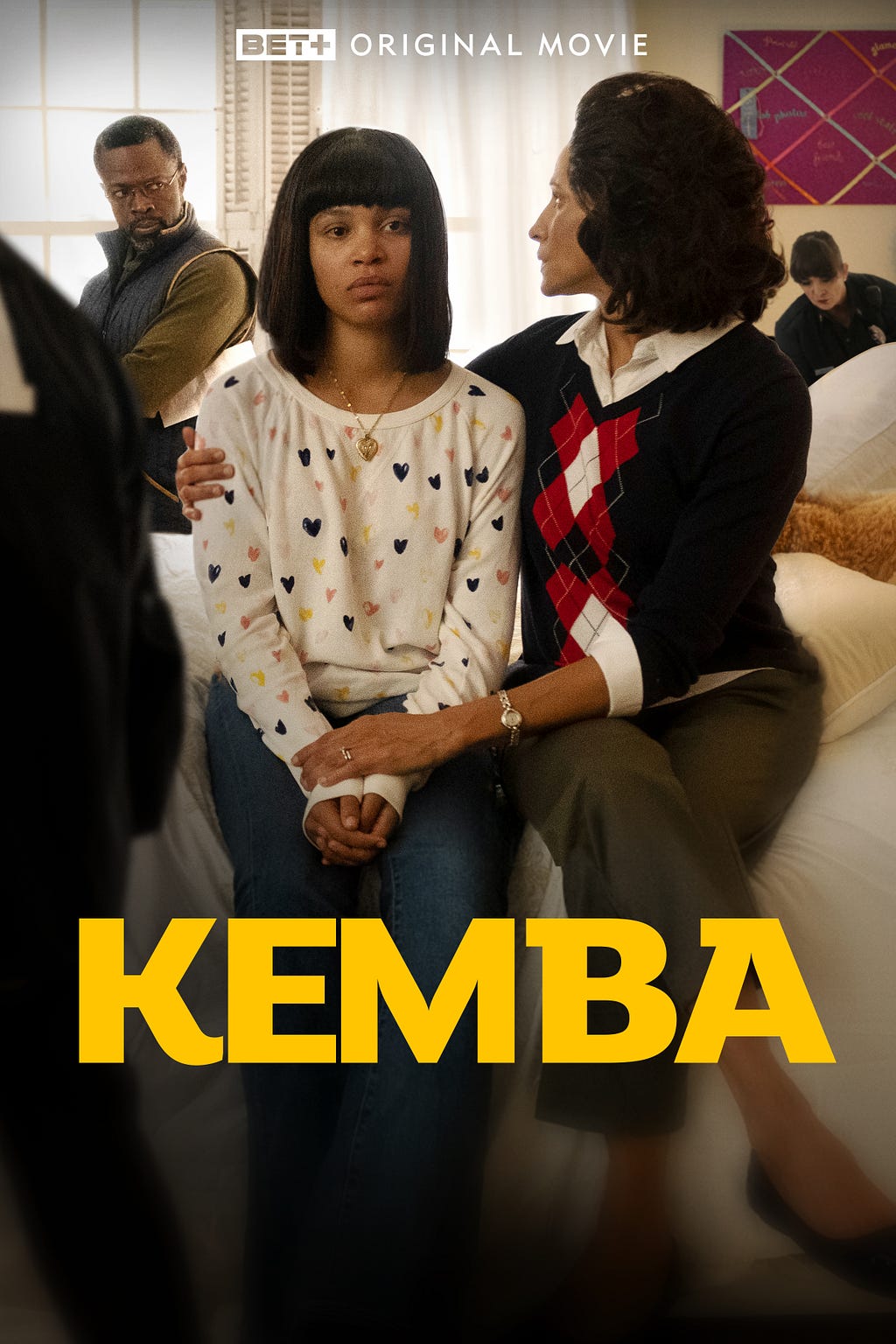

Kali’s versatility is evident in her filmography, which spans various genres. In 2023, she directed “Kemba,” a biographical film based on the true story of Kemba Smith, a college student wrongfully sentenced to decades in prison due to her boyfriend’s criminal activities. The film, which premiered at the Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival, aims to raise awareness about mandatory minimum sentencing laws and the systemic issues within the judicial system.

Kali’s work is characterized by its social consciousness. “Kemba,” in particular, serves as a tool for advocacy. The film has been screened at the U.S. Capitol and has sparked discussions among lawmakers about reforming mandatory minimum sentencing laws. Kali and her team are pushing for clemency for Michelle West, another woman facing a harsh sentence for a drug-related offense. By humanizing these legal issues through storytelling, Kali hopes to inspire legislative change and foster greater empathy among audiences.

Reflecting on her career, Kali often shares insights about the challenges and triumphs of filmmaking. She emphasizes the importance of choosing the right team, maintaining a positive set environment, and being prepared to make tough decisions to preserve the integrity of the project. Her approach is shaped by her background in anthropology, her diverse upbringing, and her early experiences in student government, where she learned the value of leadership and collaboration.

Looking ahead, Kali has several projects lined up through 2024. She continues to pitch new ideas and speak at top film programs, sharing her journey and inspiring the next generation of filmmakers. Her dedication to storytelling as a means of social change remains at the core of her work, promising more thought-provoking and impactful films in the future.

Kelley Kali’s rise in the film industry is a testament to her talent, resilience, and commitment to social justice. From her early days in Southern California to her current status as an award-winning director, Kali has consistently used her platform to highlight marginalized voices and advocate for change. As she continues to break new ground in independent filmmaking, her unique blend of cultural insights and storytelling prowess promises to leave a lasting impact on the industry and society at large.

Yitzi: It’s a delight to meet you. Before we dive in deep, our readers would love to learn about your personal origin story. Can you share your story of your childhood and how you grew up?

Kelley: My personal origin story? Wow. I don’t think anyone’s asked me to go this far back. Okay. I grew up in Southern California in the Valley. So I’m a Valley girl, but my parents aren’t. My daddy is from Alabama. So, the South, and my mom is a Pittsburgh girl. I didn’t grow up sounding like a Valley girl because the East Coast and Southern influences checked that out of me. My dad was a pastor, and my mom was an aerospace engineer, or she still is one. So, I grew up in a house of pure juxtaposition.

My dad’s African-American, and my mom is Irish-German, so I come from a mixed background. My mom’s side of the family is conservative Catholic, and my dad’s side is liberal Baptist. I grew up with this dual understanding and a lack of judgment for people’s opinions and perspectives. It was always a running joke in my family. My dad would pick me up from school on voting day and say, “Come on, honey, we need to go cancel out your mother’s vote.” So that’s the type of household I grew up in.

I think that’s what made me want to focus on anthropology when I got to college. My degree and background are in anthropology, specifically archaeology. Hence my Indiana Jones reference in the back. I’ve always been interested in cultures, our history, how we came to be, how we as people get along and don’t get along, and how we can better our relationships with each other. That field of study really spoke to me in that way.

I’ve always been a storyteller because my dad is a pastor, and those are some of the biggest storytellers every Sunday on the pulpit. He wanted me to get into politics. In fact, he groomed me for it. I ran for office since elementary school. I was part of the student government in elementary school. I was vice president of my school in middle school. I was student body president in high school. I was even president of USC’s School of Cinematic Arts all three years in grad school. That has been my journey, always working for the people and thinking about how we can make programs better.

I chose film because I told my dad that if we’re really trying to make a positive impact, it’s through storytelling. People automatically don’t trust politicians. It doesn’t matter because you have to choose a side when you’re a politician. For the most part, you have to choose a party. Then, whoever doesn’t identify with that party automatically isn’t listening to you. But what people do listen to are stories. For whatever reason, they believe what’s on TV. So why not use that tool to focus on social issues, bring awareness, and hopefully impact positive change for all of us in society?

That’s why it doesn’t matter what genre I’m directing. You’ll see that I’ve done “I’m Fine, Thanks for Asking,” which was a dramedy. Then there’s “Jagged Mind ,” a psychological time-loop thriller, and “Kemba,” a biopic. Even my short thesis out of USC, which won the Student Academy Award, was a pure drama. It’s not about the genre for me. My through line is focusing on stories from marginalized communities and those who don’t normally have a voice. If you look at all my body of work, that’s the theme. I take that from my background of growing up with very diverse parents who were still able to love each other through all their differences.

My parents were married for 41 years until my father passed away. That was not a marriage many people thought would last because of their differences. With everything going on in the world right now, between Israel, Palestine, Ukraine, Russia, and all that, I believe there’s always a way for us to see the goodness in each other. Through storytelling, it’s the most “Trojan Horse” way to sneak in a feeling, a thought, a seed to make you think and wonder if you should have some empathy or sympathy for a particular person and to humanize all of us. That’s really why I became a filmmaker in the end.

Yitzi: So you probably have some fascinating stories from all the amazing projects you’ve worked on. Can you share with us one or two of your favorite stories that kind of personify your work or personify what life is like in your work?

Kelley: Let’s see, favorite stories. I think my first feature, “I’m Fine (Thanks for Asking)”, and the way it was made is one of my most favorite stories. As filmmakers, we often think we need all the resources in the world to tell our dream story. If we don’t have the funding, then there’s nothing we can do. But “I’m Fine(Thanks for Asking)” shows that if you have grit and determination, you can get something done.

I started that film with my stimulus check and some unemployment money in the middle of the pandemic when we were supposed to be locked down. It was the summer of 2020, and no one was supposed to be outside. I called my USC friends, because I knew they weren’t doing anything, and said, “Look, let’s make a film. I’ve got a little bit of money. If we all just kick in our talents safely…” That’s why I wrote it to be primarily outside, to keep everyone safe and healthy on set.

Let me be truthful: you can’t make a feature film on just your stimulus check and some unemployment. But it became an “if you build it, they will come” situation. By taking action and attempting something like this, it caught the attention of a producer I had worked with before. She asked what I was doing and why I was outside. When I told her I was making a feature film, she wanted in and asked what I needed. I told her I needed finishing funds, and she said she would get those for me. Sometimes you just need to move and get started, and have faith that it will work out.

A lot of us can get really scared to take that leap of faith to make something we’ve been wanting to make or to get our dreams out there because we’re waiting for the perfect time, the perfect moment. But there will never be a perfect moment. There is just now, and you have to jump and do it. I didn’t expect that film to get accepted to South by Southwest and win. My mind was blown. All I wanted to do was tell a story reflecting the issues of housing insecurities that we were facing, not only before the pandemic but especially during it, particularly for women. I saw a lot of women on the streets with kids, which is dangerous because they’re at risk of having their kids taken away. That was important to tell.

My dad used to say that your greatest resource isn’t always money; it’s people. If you have people, you don’t need money. If you all come together and agree on a focused mission, you can pull together each person’s resources and make something happen. “I’m Fine( Thanks for Asking) was certainly a community effort.

With Jagged Mind, I was proud of bringing more diversity into it. It’s an LGBTQ+ film. When I got the script, it already had that level of diversity with the story of two women, which I liked because it wasn’t about them finding themselves as gay women. They were already set in who they were, just a regular couple having some time loop issues. The script originally took place in New York with two white women in a Manhattan art gallery. I thought we needed to make it different. If there were going to be art elements, let’s implement some Afro-Caribbean art. And since there’s a magical element in the film, why not set it in a place where magic is believed? I pitched New Orleans, so if anyone’s wearing a stone, you might wonder if they’re time looping you.

We couldn’t shoot in New Orleans and ended up in Miami, where I insisted it take place in Little Haiti. I love Haitian culture and wanted to be careful that if we brought in Haitian elements, the evil stone magic wouldn’t be associated with Vodou because Vodou is a religion and needs to be respected. So, we introduced new characters and hired Haitian actors. There was a time when it looked like we couldn’t find the right actress, but I reached out to another South by Southwest film director , and he connected with the lead actress from his beautiful Haitian film, and she nailed the audition. As a director, you have to do the extra work to honor the people whose stories you’re telling. I was proud we got Haitian Creole in the film, which you don’t often see or hear in a Hulu movie.

Kemba has been phenomenal in making political change. We’re advocating to President Biden to grant more clemencies especially for women with nonviolent first offenses. So we screened at the U.S. Capitol, and spoke to Congress members about mandatory minimum sentencing laws. It was a packed theater, and rumor has it we’re being invited to the White House. We’re pushing for clemency for Michelle West, a character in the film who is based on a real person who is still incarcerated. The film helps bring awareness and change to these issues. People don’t resonate with numbers and statistics, but when you put a face and story to those numbers, you get a lot of support.

So, even though these projects are different, they all have the through line of making a positive social impact, or at least I hope they do.

Yitzi: Amazing. It’s been said that sometimes our mistakes can be our greatest teachers. Do you have a story about a humorous mistake you made when you were first starting filmmaking and the lesson you learned from it?

Kelley: Humorous? I don’t know if it was funny, but I’ve definitely learned to be very careful about choosing your crew if you have the ability to do so. You don’t always get that choice, but if you do and you start to feel some sort of toxicity, you need to nip it in the bud immediately.

What happens is that we all want to be nice and try to make it work. We think, “Oh, maybe they didn’t mean it,” and start ignoring all the signs that will affect the team. It’s like a rotten apple in a barrel; it will affect the rest of the team, and you won’t be able to keep it separate. The venom will spread.

I made a mistake before by hiring people whose personalities didn’t mesh well. I was advised early on to cut them loose, but I thought, “No, they’re good people. They deserve another chance.” Oh, hell no. Never again. I learned my lesson on that. We barely finished the project. It still did well, but there was a point where the whole crew was planning a coup d’etat. They were going to walk.

But then one of them came up to me and said, “The whole crew was going to quit today, but they saw how hard you were working, and they decided not to leave you.” The other people were driving them crazy, and they were ready to walk. You don’t want to put people in that situation where they don’t feel good coming to set. You want to make sure that the environment feels good and people want to show up.

From that experience, I’ve always made sure my sets feel great. If I have control and sense something that might end up being venomous to the rest of the crew, I have no problem cutting it out. I’ve got scissors everywhere now — snip, snip. That’s something I’ve definitely learned.

I truly advise any young filmmakers: if you have control in choosing your team, choose wisely. Make sure everyone is healthy mentally on set. You don’t want anyone draining your team. It’s just not worth it. I don’t care if you get along with them, but no one else does. You have to think of the team.

Yitzi: So please tell us a bit about Kemba. Sounds amazing. Tell us why we all have to watch it.

Kelley: Oh gosh. Kemba is based on a true story about a woman named Kemba Smith in the 90s. Can you believe that’s considered a period piece now? I’m like, wait, what do you mean the 90s are a “period”? What happened? But yes, we shot a period piece set in the 90s.

Kemba was in college at the time, a very sheltered girl from the suburbs. Her parents were both educated. She met a guy she thought was great. He even mentioned that he was considering law school and things like that. Eventually, she realized he was a kingpin. By then, he had met her parents, knew all about her, and had threatened to harm her parents and her. He had beaten her several times, so she had no reason not to believe him. He even killed his best friend for thinking he was talking to the police. If he could do that to his best friend, Kemba knew he wouldn’t hesitate to do the same to her.

She ended up stuck in this relationship, and when he was killed, she was held accountable for his crimes. Even though the prosecutor even stated that Kemba never handled, used, or sold any of the drugs he was distributing, because of our mandatory minimum sentencing laws and conspiracy laws, she was tried for his crimes. The prosecution was able to tack on time and drug weights that dated back to when she was in high school as a minor and didn’t even know him and they were able to issue that all due to our conspiracy laws.

She was given 255 kilograms of crack cocaine distribution. At that time, the disparity between crack and cocaine sentencing was 100 to one. She ended up getting 24 and a half years in prison for something she did not do, just because she was caught up in it.

During her trial, the domestic violence expert testified, but the judge fell asleep. This old white Virginia judge fell asleep probably because he was treating her like another number and also that he knew mandatory minimum sentencing laws meant he had to give her the mandatory minimum anyway. It removed his discretion to consider her individual circumstances. He wasn’t the nicest judge, so who knows what he would have done even if he had the choice. But the bottom line is, he still had to follow the mandatory minimums. Who cares about a domestic violence testimony, right?

Her story is phenomenal. We’re using it to advocate for clemency for Michelle West, who’s also featured in the film. Michelle received a double life sentence plus 50 years for a first-offense drug case with a murder involved. The actual shooter is out, but she has a double life sentence plus 50 years. This over-sentencing, especially of women, is rampant. Many women incarcerated are first-time offenders, and their crimes are often in association with men who did them.

Michelle has already served over 30 years, and we’re really pushing for her clemency this year by using the film. We hope to move hearts and get her home to her daughter, who lost her mother to this system when she was 10-years-old. They haven’t been together for decades. Kemba brings light to these issues and helps push for changes in the justice system.

Yitzi: In your ideal world, in your dream world, what do you wish would change as a result of people’s hearts being impacted by your film Kemba ? What’s your dream impact?

Kelley: Yeah, well, there’s a lot of impact that I want to happen. First, it’s a cautionary tale for parents and young people who are going off to college or wherever their next adventure is in life. Many people are sheltered, and even those who aren’t often don’t realize these laws exist. They think that because they’re not directly involved in something illegal, they’re exempt. But if their friend, roommate, boyfriend, or girlfriend is involved, they can still be affected. Many people don’t know about these conspiracy laws until it’s too late and they’re convicted for crimes they had nothing to do with.

It’s important for people to know about these laws and to be mindful of who they surround themselves with. Parents need to be aware of these dangers as well. Additionally, we need to bring more awareness to mandatory minimum sentencing laws and reevaluate them. Quite frankly, these laws are lazy. They don’t take individual circumstances into account because that would require effort. It would mean listening to domestic violence testimonies, humanizing people, and understanding that mistakes can happen, whether it’s the first or second time. It would require considering what led someone to make a mistake. But instead, we just sweep everyone under these mandatory minimum sentencing laws, and we know which communities end up targeted: communities of color and impoverished communities.

These are the ones suffering because they don’t have what Kemba had, like the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and other organizations. Kemba had an army to help her, and she barely got out by the skin of her teeth. Imagine what happens to those who have nothing and come from very little. Who’s fighting for them? That’s why films like Kemba help bring awareness. For people who can’t afford such advocacy, we’re pushing to advocate for them as much as we can.

Yitzi: This is our signature question. So, you’re a social impact filmmaker. Can you share with our readers, based on your experience, the five things you need to be a successful social impact filmmaker?

Kelley: Patience. Patience, a lot of it, because social impact stories aren’t what people are waking up on Saturday morning wanting to watch. They’ve had a long week, and no one wakes up on Saturday saying, “You know what I want to see? A movie on mandatory minimum sentencing laws.” Nobody does that. So, first, you have to have the patience and understanding that getting stories like this made can be challenging. But there are organizations out there, like our producers at Moving Picture Institute and BET, that came together and said, “This is important, and we want to get the financing for this.” So, it does exist. You have to have the patience to find them.

Second, you have to have a heart. This ties into my anthropology background. We’re taught as anthropologists to remove our biases, at least the ones we’re aware of. You can’t remove the implicit ones, but you can work on the ones you’re aware of. When doing work like this, you have to remove what you think is right and be able to listen objectively to people that society might deem as on the fringes or not ideal citizens. When you listen with an open and objective heart, you can find the humanity in people and see them for who they are.

Third, I would say stamina. Patience and stamina go together, but there’s an exhaustion that comes from making films with heavy subject matters. My film, Lalo’s House, was about child trafficking in Haiti. I spent over 10 years investigating real child trafficking issues there. After making that film, I was mentally exhausted. Seeing children abused for so long is heartbreaking and wears on you. You start to wonder if the subject matter you’re covering is too big to ever change.

Fourth, having faith that your little poke in the system will make a difference. It might inspire someone who saw you poke to get their own needle and poke too. It’s a trickle effect. Just because you have one thin little needle doesn’t mean it won’t put enough holes in a system that needs to change. Keep poking and hopefully, others will join in. It may feel overwhelming, but it takes time to turn a ship, and a ship can turn.

Fifth, be yourself and protect your light. You’re dealing with many people when making films, not just challenging subject matter. It’s easy to get lost trying to adapt to what others want because you want something made so badly. But if you stay true to yourself, you’ll make stories that matter. If you want to make social impact stories, you’re already different. You have a truth within you that you’re standing on. When pitching ideas, stand in your truth because you have this in your heart for a reason. Don’t try to guess what others want. Trust that what you bring to the table is valuable and valid. Don’t second-guess yourself. Bring your ideas, stand on them, and be proud, whether you get it made or not. It just means you’re meant to be in another place, and you will find your right tribe. Trust that.

Yitzi: So inspirational. This is our final aspirational question. Kelley, because of your amazing work and the platform you’ve built, you’re a person of enormous influence. If you could spread an idea or inspire a movement that could bring the most good to the most people, what would that be?

Kelley: There are so many important movements, but for me, because I was an archeologist, there’s a particular movement I find crucial. The running theme with people of color is that we don’t have control of our own narrative. Many others are telling our stories. It’s one thing in film, but in our history books, our stories are being erased. Look at what’s happening in Florida. Books are being taken out of schools, and kids aren’t learning about our history.

We have to consider who writes these books and where they get their information. Our history begins in the dirt, with archeology. Who is excavating it, writing about it, and verifying these stories through excavations? When I used to present our findings at the Society of American Archeology, the largest convention of archeologists in the U.S., I would look around and see that my partner and I were the only people of color there. Not just Black people — there were no Asian or Latin people either. It was primarily white men with very few white women.

Every presentation was about people of color: Native Americans, Asians, Africans. But there wasn’t anyone from those cultures presenting or supporting it. It’s fascinating to me because I don’t want to discourage interest in other cultures. We need better understanding and ways to communicate through our differences. So, I’m not trying to discourage any white folks from doing archeology, but when you do it, bring up someone from that culture. Teach them what this is because, in many of our households, nobody is talking about archeology.

If you really love South Asian Pacific culture, take in a South Asian Pacific kid and teach them archeology. They’ll have insights that you don’t about the nuances you’re writing and interpreting. In our colleges, especially in Historically Black Colleges and Universities, we are losing archeology and anthropology classes. They are not being funded anymore, which is crazy because we are some of the biggest voices saying we don’t have control of our narrative. But they’re taking out the historians and future people who will confirm and preserve our history and culture.

I have Indiana Jones in the background here. Indiana Jones was a big influence on why I wanted to become an archeologist. I have another concept that reflects more people of color in archeology. I’m hoping this concept will lead to a revival of interest in archeology, where people can finally see themselves doing it through our inclusive depiction and casting. I want it to be big, like Indiana Jones, to inspire another generation to become archeologists and confirm and preserve our history and culture starting in the dirt. So, my biggest mission through filmmaking is telling this story.

Yitzi: Thank you so much for this. How can our readers watch your films? How can they purchase anything to support your work?

Kelley: Oh, yeah. Thank you. My original scrappy feature film, which is a great reference for new filmmakers who want to see how scrappy you can be and still get distribution, is on Amazon. It’s called “I’m Fine( Thanks for Asking)”. You can find that on Amazon.

“Jagged Mind”, the LGBTQ+ psychological time thriller, is on Hulu. Kemba is on Paramount+/ BET+ right now.

You can always reach out to me. I’m very active on Instagram, so @iamkelleykali on Instagram. I try to get to people’s questions, especially if they’re filmmakers, artists, or storytellers, but of course, you don’t have to be. If you message me, please have patience because it sometimes takes me a minute.

Yitzi: It’s been truly, truly amazing meeting you. I wish you only success.

Kelley: Thank you. Thank you for all that you’re doing to get our voices out there as filmmakers as well. I really appreciate the work you’re putting in, Yitzi.

Filmmakers Making A Social Impact: Why & How Kelley Kali Is Helping To Change Our World was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.