…One of the most guiding principles for us, which I wish I knew 10 years ago but am glad I know now, is to choose those who choose you. You can spend your entire life chasing people, things, and opportunities that don’t value or validate you, which only highlights your shortcomings. But if you stop and look around, you’ll realize there are already people close to home rooting for you, and there are opportunities through those close ties where you will be put forward on the right foot. The best example of this for me was Dikega. We had been friends in childhood and through high school, and then in our twenties, we went on separate paths — Dikega in film and me in music. But Dikega, who I call Deke, was insistent multiple times. He calls me Jin, and he said, “Jin, we’ve got to collaborate on something. We’ve got to work together.” At the time, I was still touring and distracted by many things that come with the music world. But finally, I heard him because he was choosing me. He was listening to something bigger than us about how we had a destiny to work together and that the things we could create together would be truly great…

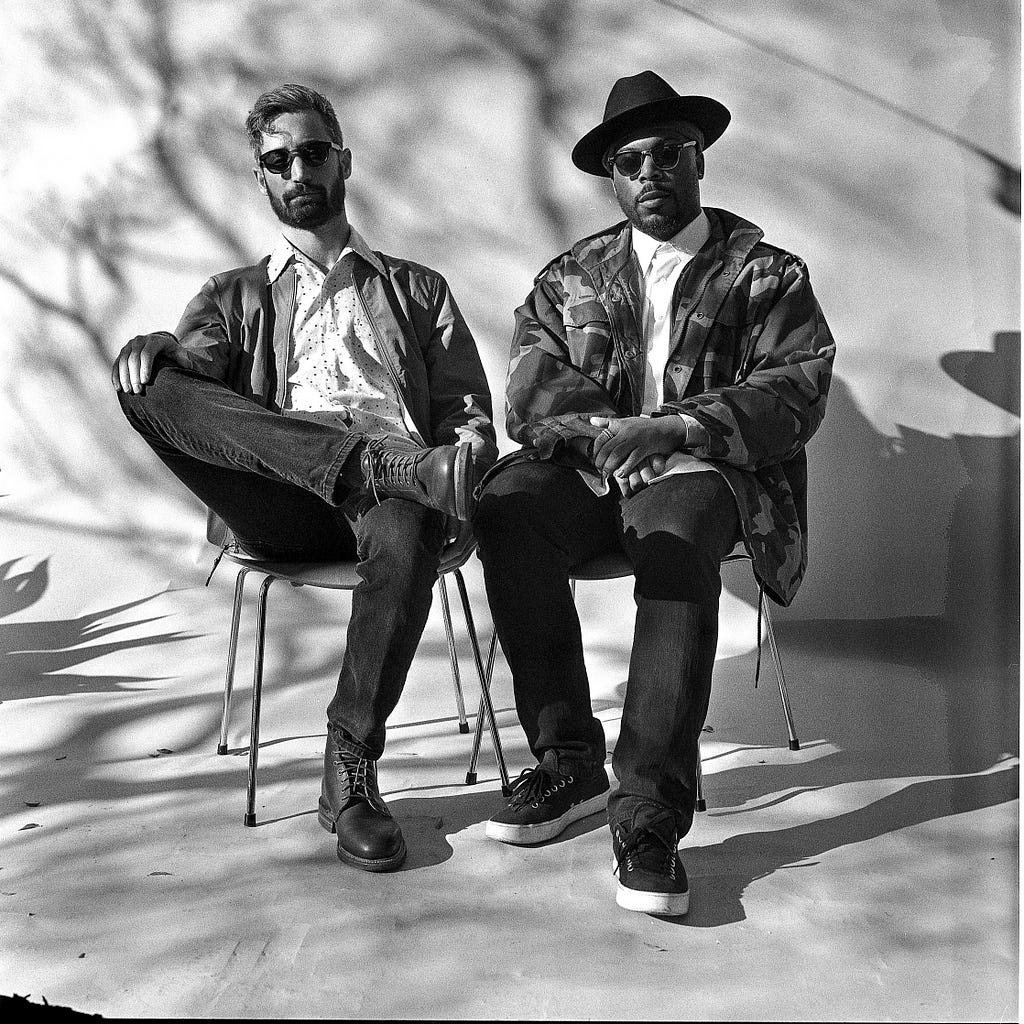

I had the pleasure of talking with Spencer Mandel and Dikega Hadnot.

Spencer Mandel, an accomplished writer and filmmaker, has built an impressive career rooted in a long-standing friendship with co-writer and director Dikega Hadnot. Their creative partnership culminated in the production of their award-winning short film “Little Brother” in 2019, a testament to their shared vision and storytelling prowess.

Spencer Mandel was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. He comes from a family deeply entrenched in the medical field, with his mother, father, grandfather, uncle, sister, and brother-in-law all practicing medicine. Despite this strong familial inclination towards healthcare, Mandel pursued a different path. From an early age, he exhibited a passion for reading and writing, completing a book of poetry by the second grade. His artistic streak, possibly inherited from his mother who later discovered a talent for oil painting, set him apart in his family.

Mandel’s academic journey took him to Oakwood School in the San Fernando Valley, where he met his lifelong friend and future collaborator, Dikega Hadnot. In 2005, Mandel attended Brown University, majoring in International Relations while continuing to nurture his love for music. He received a bass guitar as a Bar Mitzvah gift, which sparked a passion for the instrument. This led to the formation of a rock band in Providence, Rhode Island. Music remained a significant part of his life throughout college and beyond, with his band, Incan Abraham, gaining national attention and critical acclaim.

During his college years, Mandel also broadened his horizons by studying abroad in Barcelona, where he immersed himself in the local culture. After graduating, he balanced his musical pursuits with writing, contributing to publications such as WhoWhatWhy, Guernica, and Rogue. His journalistic work allowed him to refine his writing skills, which would prove invaluable in his future film projects.

Mandel and Hadnot’s collaboration officially began in 2016 when they reunited to write a pilot inspired by their archaeological dig experience. Recognizing the unique synergy between Mandel’s writing and Hadnot’s directing and producing skills, they decided to embark on a more ambitious project. This led to the creation of “Little Brother,” a short film developed during a creative retreat in Topanga Canyon. The film, praised for its vivid storytelling and social relevance, highlights their ability to address complex themes through nuanced narratives.

Their writing and directing partnership, Gonzo Griot, reflects their diverse backgrounds and shared vision. The name combines “Gonzo,” representing an exploratory and sometimes absurdist approach to Americana, with “Griot,” symbolizing their commitment to mythological, historical, and ritualistic storytelling.

Mandel’s professional journey is marked by a series of significant achievements. As a writer, he has crafted multiple feature scripts and TV drama pilots, showcasing his versatility and depth. His collaboration with Hadnot has produced critically acclaimed content that resonates with audiences and industry professionals alike.

The duo’s film “Little Brother” was shot in Los Angeles, reflecting their deep connection to the city and its evolving cultural landscape. They aimed to portray the complexities of LA, emphasizing the impact of gentrification on historic black and Latino neighborhoods. This focus on location and authenticity is a hallmark of their storytelling approach.

Looking ahead, Mandel and Hadnot aim to expand their creative horizons. They aspire to produce gritty, narrative-flipping historical dramas with mid-level budgets, blending genres such as American revenge thrillers, foreign cinema, and magical realism. Their goal is to create impactful, thought-provoking content that challenges conventional narratives and fosters empathy and understanding among diverse audiences.

Spencer Mandel’s journey from a creative childhood in Los Angeles to a successful career in film and writing is a testament to his dedication and talent. Alongside his lifelong friend Dikega Hadnot, he continues to push the boundaries of storytelling, creating films that resonate deeply with contemporary audiences. Their partnership, rooted in a shared history and vision, promises to bring innovative and socially relevant narratives to the forefront of the film industry.

Dikega Hadnot, an emerging name in the film industry, has recently made headlines as co-writer and director of the award-winning short film “Little Brother.” Born and raised in South Los Angeles, Hadnot’s background is as diverse and dynamic as the city he calls home. His journey from a curious child to a celebrated filmmaker is a testament to his passion, resilience, and the power of long-standing friendships.

Dikega Hadnot was born to a Liberian mother and an African-American father. In 2005, Hadnot chose to attend Johns Hopkins University, turning down a full scholarship to the University of Southern California. At Johns Hopkins, he pursued film theory and production, laying the academic groundwork for his future career. After graduating in 2009, Hadnot gained invaluable experience working as an assistant to renowned filmmaker Terrence Malick and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki on the films “Tree of Life” and “To The Wonder.”

Hadnot’s early career was shaped by his time with Malick and Lubezki. He recalls a pivotal moment on the set of “To The Wonder” when Malick entrusted him with directing a scene featuring Olga Kurylenko. This experience, Hadnot notes, was a significant confidence booster and an early validation of his directorial instincts.

Returning to Los Angeles, Hadnot transitioned into producing music videos for Interscope Records, working with artists like Iggy Azalea, Nipsey Hussle and Azealia Banks. Concurrently, he continued to nurture his passion for music through his hip-hop project, Maya Angeles, which received airplay on KCRW.

In 2016, Hadnot reunited with Spencer Mandel to form their writing and directing partnership, Gonzo Griot. The duo is represented by Original Artists, and Jackoway Austen Tyerman Wertheimer Mandelbaum Morris Bernstein Trattner & Klein LLP. Their partnership led to the creation of “Little Brother,” a short film that has garnered significant acclaim.

“Little Brother” emerged from a creative retreat in Topanga Canyon, where Hadnot and Mandel brainstormed the idea over a night of wine, deejaying. The film, set against the backdrop of Los Angeles, addresses themes of sociocultural tension, the pressures of urban life, and the quest for shared humanity in a divided world.

Hadnot emphasizes that the themes in “Little Brother” were both meticulously planned and organically evolved. He believes that art’s beauty lies in its ability to resonate differently with each viewer, allowing personal interpretations to flourish.

The production of “Little Brother” was not without its challenges. As Hadnot explains, the film’s carefully structured and visual screenplay required a strong team and logistical precision to bring to life. Filming took place exclusively in a single location in Los Angeles, chosen to reflect the city’s rapid transformation and cultural loss.

Despite the hurdles, Hadnot and Mandel’s dedication paid off. The film was praised by judges at Film Pipeline for its vivid storytelling and social relevance, setting the stage for future collaborations between the longtime friends.

Hadnot and Mandel continue to explore new creative avenues. Their feature debut, “Break,” follows the story of Eli, a young man in Detroit who finds solace and purpose in an old pool hall. Released on Amazon Prime Video, the film features a diverse cast, including Darren Weiss, Jeff Kober, and Victor Rasuk.

Looking ahead, Hadnot is excited about “Do Not Enter,” a film based on the young adult thriller novel “Creepers,” set for release later this year with Lionsgate. The duo also aims to produce an original feature film, with Hadnot stepping fully into the director’s role, embracing the “cowboy” spirit instilled in him by Malick.

Throughout his career, Hadnot has remained grounded in his diverse cultural heritage and the storytelling traditions of his West African and African-American roots. His approach to filmmaking is deeply influenced by his experiences and the people he has met along the way.

Hadnot’s advice to aspiring filmmakers is to maintain a balance between their career and personal life, listen to their intuition, and embrace both divergent and convergent thinking. He advocates for a guiding philosophy in creative endeavors, one that serves as a cornerstone during challenging times.

As he continues to carve out his niche in the film industry, Dikega Hadnot remains committed to creating stories that inspire empathy, understanding, and communication. His journey from a curious child in South LA to a filmmaker on the rise is a testament to the power of passion, perseverance, and the enduring bond of friendship.

Yitzi: Spencer and Dikega, it’s a delight to meet you. Before we dive in, our readers would love to learn about your personal origin stories. I guess we’ll start with Dikega first. Can you share with us the story of your childhood and how you grew up?

Dikega: Sure. First of all, thank you for having us, Yitzi, we really appreciate it. Well, I grew up in Los Angeles, moving around the city from the west side to the northeast side, to the south side, so I really got to see the whole city. I went to school in the valley, actually, where Spencer went to school too. I come from a bi-ethnic background; my mother is West African and my father is African American. I just grew up as a cosmopolitan kid, really going around the city, attending school in the city and in the valley. That school had a strong art background and electives, and that’s what led me to where I am now. I took film and video classes, drama, writing — anything related to narrative, story, people, and film.

From there, I tried to meld it with the cultural heritage my mom gave me. Being from West Africa, they have a strong background in oral storytelling. So, I went to Johns Hopkins University. I really wanted to study film. My mom and I went back and forth about it. I actually got into USC, but I really wanted to study film, so we fought about that. I went to Hopkins and studied film there. That’s the abbreviated version of my childhood, where I come from, and my interests.

Yitzi: Amazing story. How about you, Spencer?

Spencer: I’m from LA as well. My entire family is in the medical field — mom, dad, grandpa, uncle, aunt, and now my sister and brother-in-law. I’m the sole artist in an entirely medical family. The art streak is something that was in my mom, but it was unexpressed for a long time. Since COVID, she’s finally had some time to learn to paint, and she’s an incredible oil painter now. So, I don’t think my artistic side came entirely out of nowhere.

I’ve always loved books, words, and stories. My exposure to film began at our school in the Valley, where I met Dikega in first grade. In 10th grade, we started taking these film and video classes that were really good. We watched films and learned how to edit on VHS tapes, which was my first real exposure to film.

Growing up in LA in the 90s, during the empire era of Hollywood, my dad, a doctor, and my mom had a lot of patients in the entertainment business. We were exposed to the old world of Hollywood and the big premieres, so it was always around us. I think, subconsciously, that exposure, plus watching the great films of the 90s, like Jurassic Park, which was both intelligent and a blockbuster, influenced me. The Disney movies of that era were also so good and so big. They combined art and business, which was pretty foundational.

Our school, Oakwood, was a college prep school, but it was almost like an art school. It was a topsy-turvy world where all the cool kids played music, and the nerds played sports. Not to oversimplify, but Dike did some track and field, and he was not a nerd — one of the coolest guys. We all had to learn an instrument, so I learned bass. I went to Brown to study international relations, but my main extracurricular was my band. I was always going to New York and playing shows there. Music was a major thing for me through my 20s. I had a band, we toured nationally, and we were featured in Pitchfork, Spin, Time, and had a Red Bull publishing deal. So that was the first chunk of my life.

Yitzi: Dikega, you probably have some amazing stories from your filmmaking career. Can you share with the readers one or two of your favorite memories or anecdotes from your professional life?

Dikega: Definitely. One of my earliest and fondest memories is working with Terrence Malick and Emmanuel Lubezki, who are film luminaries. I worked on Tree of Life and To the Wonder. On To the Wonder, I was the assistant to Emmanuel Lubezki, the DP of that film. Terrence was testing all these new camera formats because the technology was shifting, and there were many different digital varieties to try.

He was shooting a scene with Ben Affleck and needed another scene shot with the co-lead, Olga Kurylenko. We were on set, and there was a pause. One of the producers came up to me, and I was just a little assistant at the time. He said, “Deke, Terry wants to speak to you.” I thought, “Oh man, what did I do? I don’t want to be fired.” He took me over to Terry, and Terry said, “Deke, I want you to go shoot a scene with Olga Kurylenko.” I thought I was dreaming. I was only 20 or 21 at the time, and I was like, “What?” He repeated, “Yeah, you heard me. I want you to go shoot a scene with Olga Kurylenko. We’ll be shooting with Ben.”

So many emotions went through my head because this is one of the best filmmakers of all time, a director’s director. I went back to Emmanuel Lubezki, Chivo, and said, “Terry wants me to shoot a scene.” He replied, “Yeah, fine. Go ahead.” I asked him, “What do I do?” and he said, “Well, ask him.” So I asked Terry, and he just said, “Be a cowboy,” and that’s all the direction I got. With that, I went to shoot Olga Kurylenko with two other young assistants. It was crazy — my first introduction to film, shooting one of the Bond girls on a Terrence Malick film. I don’t know if it made it into the film, but it was probably the coolest experience.

Another fond memory is working with Bruce McKenna, the creator of The Pacific and an Emmy winner. Having that experience with such a great mentor, working hands-on, crafting an original historical war drama with him was incredible. Early in my career, having someone like that to guide and mold you, and also give you life experience and advice, was invaluable. There may be other stories with actors and actresses, but these two experiences — working with these great people and getting to know them as individuals — stand out the most.

Yitzi: Amazing stories. Spencer, it’s been said that sometimes our mistakes can be our greatest teachers. Do you have a story about a humorous mistake you made when you were first starting and the lesson you learned from it?

Spencer: This is a pretty simple one, which I think you would relate to as a journalist. When I was fresh out of college, I had a side job alongside my band. I was a staff writer for a publication. For my first piece, an investigative journalism article, I wrote it just like a college essay. I had thrived in the academic lane up till 22, so I wrote it like a college essay.

At this publication, as a favor, there was an editor from the New Yorker who was pro bono doing some editing consult. He got a hold of my piece and redlined almost all of it. I could see nothing but red, with maybe little sprinkles of my original words left. This crushed my Ivy League ego pretty hard. I thought, “What am I doing wrong?” He told me, “You’re writing like an essay. This is journalism. Get to the point, use shorter sentences, and aim for clarity.”

Then I recalled one of my heroes, Hemingway, who redefined prose by writing for clarity. As he would say, it’s important to know the $10 words but use the $1 words.

Yitzi: Great. Beautiful. Both of you have so much impressive work. Can you share with our readers the exciting projects that you’re working on, what you’re releasing now, and what you hope to be working on in the near future? Dikega, do you want to start?

Dikega: Yes. Our original-penned feature debut, Break, follows Eli, a young man in Detroit trying to support his family. He stumbles upon an old Detroit pool hall where his father used to hustle and decides to follow in his father’s footsteps. It just came out on digital on Amazon a little over a week ago. You should check it out. It features the wonderful Darren Weiss, Jeff Kober from Sons of Anarchy, Victor Rasuk from Lords of Dogtown, and many other great actors. We also have another film called Do Not Enter, based on the young adult thriller novel Creepers, which should be releasing later this year with Lionsgate.

Spencer: Yeah, we have some other things in the works that we’ll talk about soon as they’re a bit farther along. One of our main goals is an original feature where Dikega can finally step into the director’s seat, not just the writer’s desk, and be a cowboy as Terry taught him to be. We shot a short film, which was our first chance to showcase Dikega’s directorial skills. I wasn’t even sure what his director archetype would be, but when it was go time, he just put on his gaucho hat that evoked a cowboy spirit, and he did it. I could feel the spirit of what he learned firsthand channeling through him. I can’t wait to see him do that for a feature.

Yitzi: So talking about Break for a second, Spencer, what would you say are the lessons that society could take from the motifs of the film?

Spencer: I think there are a lot of good things. We’ve been told that the film has some great values, which we tried to instill in a grounded way that isn’t naive or cheesy. One of the biggest values in the film is that it takes a village — a chosen village. That can be people of all different backgrounds, just like Deke and I are parts of each other’s village. I think that’s one of the most important values.

Dikega: Another one is stated by Eli’s sister in the film: it’s okay to not be okay. In our fast-paced society and with the rise of anxiety, people sometimes forget to stop and check in with themselves. It’s important to realize that if you’re not okay at the moment, that’s fine. You can rebuild yourself and go back out there. It’s a simple theme we emphasize in the film, but it’s one many people forget. Spencer, Darren, and I talked about this a lot.

Another theme is that you never know why people are doing what they’re doing or why they’re present in your life. It’s important not to judge a book by its cover. Try to have empathy and understanding before making a judgment. That’s another key message we wanted to convey.

Yitzi: This is our signature question. You’ve been blessed with a lot of success now. Looking back to when you first started, can you share five things you know now that you wish someone had told you when you first started?

- Dikega: Yes. One thing I learned a bit later in our journey is this: Don’t make your career your entire life. You need to have a full palette of life that includes your village — your family, friends, social circle, whatever it is. All that needs to be there. Exercise, gym, whatever it is, especially if you’re doing really demanding work or you’re in a field like entertainment, where you’re really a mental athlete. It’s super demanding with tight deadlines and everything. You have to find respite in other aspects of your life. Don’t over-identify with your career. Maybe that’s the simplest way to say it.

- Spencer: One of the most guiding principles for us, which I wish I knew 10 years ago but am glad I know now, is to choose those who choose you. You can spend your entire life chasing people, things, and opportunities that don’t value or validate you, which only highlights your shortcomings. But if you stop and look around, you’ll realize there are already people close to home rooting for you, and there are opportunities through those close ties where you will be put forward on the right foot. The best example of this for me was Dikega. We had been friends in childhood and through high school, and then in our twenties, we went on separate paths — Dikega in film and me in music. But Dikega, who I call Deke, was insistent multiple times. He calls me Jin, and he said, “Jin, we’ve got to collaborate on something. We’ve got to work together.” At the time, I was still touring and distracted by many things that come with the music world. But finally, I heard him because he was choosing me. He was listening to something bigger than us about how we had a destiny to work together and that the things we could create together would be truly great.

- Dikega: Thinking about what Spencer just said made me think of another one, which is to listen to your intuition. I’m sure many people say this, but it’s super important. We’re an intelligent species with big brains that can process and think a lot, but we can get caught up in our intellectual, cerebral mind. Listen to your intuition and know when to switch it. Take note of your gut feeling first before moving over to your intellectual brain to parse how to communicate it. So, gut first, then intellect.

- Spencer: I learned this in my band, and it’s valuable in my new band with Deke. There is a time and place for both divergent and convergent thinking. In the arts, divergent thinking, open-mindedness, and radical approaches are often called for more than in other fields. But even in the arts, you need to converge. How are we going to finish it? How are we going to pay for it? Who are the people that can execute each part of the process? That’s very important too. In my band, I learned that if you’re in the middle of a jam or trying to write a song together, it only works if everyone is in the same mindset at the same time. If some people are in divergent thinking mode and others are in convergent thinking mode, you’ll be speaking different languages. Some people will want to explore, brainstorm, and jam, while others will want to complete the chorus or the C section. This can cause conflict, which is totally avoidable and unnecessary. I wish this was taught in school because these modes are so different. You might call it right brain and left brain, but you need the full brain to complete a great piece of work.

- Dikega: Piggybacking off of Spencer again, set a guiding philosophy for whatever endeavor you start on. It’s paramount for success. That philosophy should act as a cornerstone you always return to when things get hairy, which they will. So, I think that’s the most succinct way I can put that.

Yitzi: So this is our final aspirational question. I’ll ask it to each of you. Both of you are people of enormous influence because of your great work and the platform you’ve built. If you could spread an idea or inspire a movement that would bring the most good to the most people, what would that be?

Dikega: Well, I think if I remember correctly, excuse me if I ramble a bit, but with art, since it appeals not just to our intellect but also to our emotional body, art allows us to enter into other people’s shoes and see their perspectives. This theme is present in Break — having empathy for others. In terms of a movement, I think our work aims to inspire people through art to foster greater communication between people and groups. Art is communication. A lot of people forget that and get caught up in the smaller details or the emotional aspects or even the craftsmanship. But in the end, it’s a communication tool. If that communication can be used to inspire more humanity and discussion, that would be the movement.

Spencer: I think Dikega put it well. I would just emphasize the heightened importance of putting humanity first, especially now that technology is taking over our lives and our world. Artificial intelligence is complementing in some cases but also threatening almost every career, and it will change everything about how we live. This is a decisive time to ensure that human values, human creativity, and human lives are at the center of all this change.

Yitzi: So beautiful. How can your readers continue to follow your work? How can they watch Break? How can they watch any of your other productions? How can they support you in any way?

Dikega: You can check Break out on Amazon Prime Video. For our other work, we have a small production company. If you want to see some of our previous branded content, short films, and other projects, you can visit www.latebloom.com . As for our upcoming projects, you’ll just have to stay tuned.

Spencer: I would say, check out Little Brother, the short film we did together that Dikega directed here in L.A. and in South Los Angeles. It’s on YouTube, and we’d love your thoughts on that too.

Yitzi: Thank you so much for your time. This has been very inspirational. I’m excited to share this with our readers. It’s been so nice to meet you, and I wish you continued success.

Spencer: Thank you, Yitzi. Hopefully, we’ll talk to you again.

Yitzi: Yeah, I’d love to do it again. Thank you. Take good care.

Spencer Mandel and Dikega Hadnot: Five Things You Need To Create A Successful Career In TV & Film was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.