Social Impact Authors: How & Why Author James Mueller of Mueller Art & Literature Is Helping To Change Our World

Reverse your perspective when you hit a wall. For example, when you can only go so far in painting a portrait, take out a mirror and look at it in reverse. Then, it’s like looking at it for the first time.

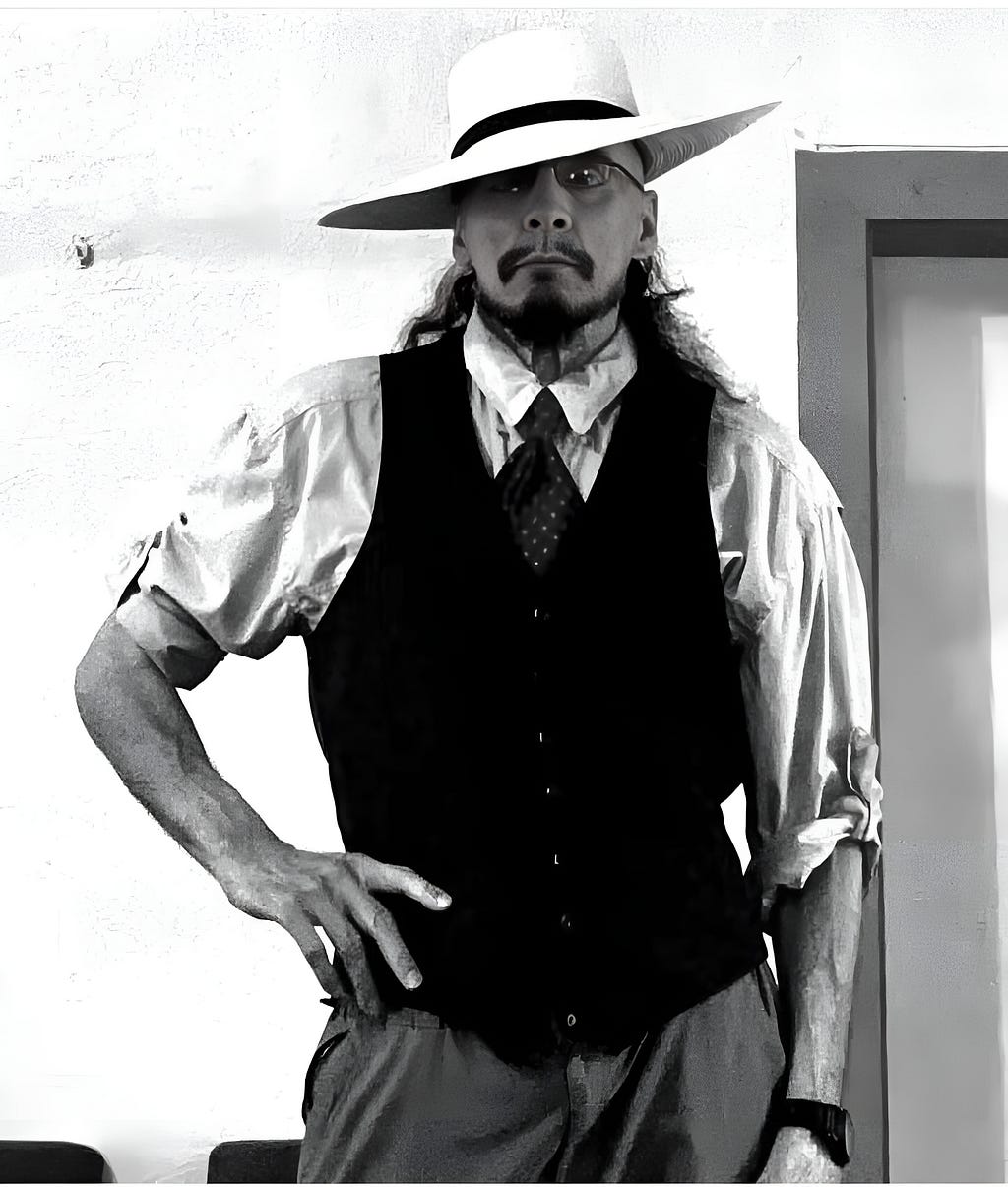

As part of my series about “authors who are making an important social impact,” I had the pleasure of interviewing James Mueller.

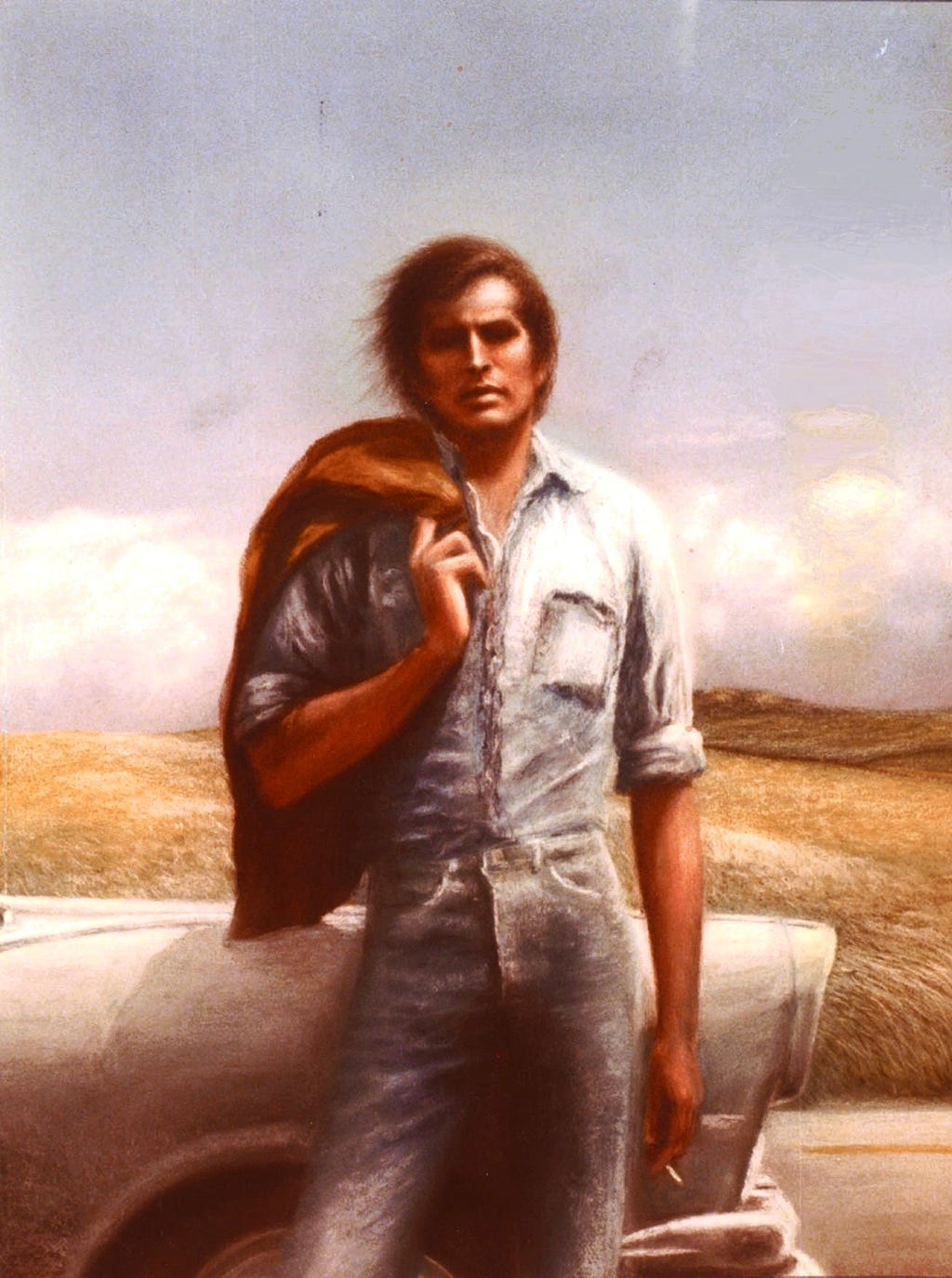

No bio of Mueller is complete without a preliminary understanding of his novel, Confessions of St. Augustine. Set against the background of hundreds of his paintings and thousands of his drawings — as diverse as Daumier and Degas, Hopper and Homer — Mueller has written a novel woven together in such a way it can only be described as a unique hybrid: a literary novel and an art book that has no rival in history of the novel — colorful, original, outrageous — the voice of a Holden Caulfield, Alexander Portnoy, Robin Williams, Jack Nicholson and yes even a Samuel L. Jackson (for starters) but the ying and yang of modern man in all his bipolar glory — wavering between Augustine and Auschwitz, Sartre and certainty — Heaven or hell… — but desperately searching for meaning with little more than his words and his Art as a means to express it. A wild manic full-throttle ride through our subconscious dreamscapes — Mueller has written a picaresque (as well as picturesque) novel in the tradition of Catcher in the Rye, Portnoy’s Complaint, and Catch-22, but with one more catch — the narrator is the artist.

Thank you so much for joining us in this interview series! Before we dive into the main focus of our interview, our readers would love to “get to know you” a bit better. Can you tell us a bit about your childhood backstory?

I was raised in New Hope, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, a famous art colony where the famous Pennsylvania Impressionists consolidated under their founder, William Lathrop, whose home we lived next to. Across the street was Phillips Mill, ground zero for much of the arts then. Famous artists, actors, musicians, and writers were so commonplace that I assumed the outside world was the same. It wasn’t until we moved that I realized my DNA of being the consummate artist would be challenged at almost every step.

Like the name, New Hope offered new hope to thousands of artists throughout the 20th century! Because my fantasies could never have flourished in any other place than New Hope. Where else could I have found such a cross-section of artists, writers, playwrights, actors, musicians, and all the other people who made my childhood ripe for all that lay before me? Any more rural, I would have missed the culture; any less rural, I would have missed the romance of America. Because the canal and the river we lived on were Tom Sawyer’s Mississippi, that led to parts unknown — adventures yet to be experienced, Indian tribes yet to be discovered. Because they were all out there, somewhere beyond that river, whether they were up the river, down the river, or across the river — or the land between the canal and the river — it was all out there — America, the frontier, the West — I had it all — right there in my backyard.

It only grew with the town’s aid, the people, and my imagination. Friday night square dances at Phillips Mill across from our place were a hangout for trappers and frontiersmen, half breeds, and an occasion for Indians like myself. The Delaware River on the canal’s other side was the wide Missouri I’d yet to cross. The hills up and beyond the mill were the Black Hills held so sacred by The Sioux.

Of course, all this occurred in that age of innocence most of us have if we’re not prematurely deprived of it, so it’s possible I would have seen it much differently if I’d been allowed to grow out of it naturally. But everything came together at the right time, and there was no better time, even in the evolution of New Hope. Shortly after we moved, it went the way of most art colonies and became less spectacular and more spectacle.

When you were younger, was there a book that you read that inspired you to take action or changed your life? Can you share a story about that?

The Catcher in the Rye changed my life more than any other novel. From then on, I was determined to continue where The Catcher in the Rye left off. I went from a dilettante to a person so consumed by the newfound passion that I never have in my 59 years since then wavered even once — often working night guard jobs while teaching full-time, night guard jobs sometimes in mosquito-infested swamps guarding some construction site — or sleepless nights at home trying to get that last sentence just right — working on an opus that only became more and more grandiose than I ever could have imagined — even to the point of creating hundreds of paintings and drawings to serve as a counterpoint in a 700-page novel that in my mind was constructed as tightly as any poem. And it all started with The Catcher in the Rye.

It has been said that our mistakes can be our greatest teachers. Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting? Can you tell us what lesson you learned from that?

Thinking I could become “normal” by majoring in psychology. You see, almost all through school — right up to when I graduated from college — my notebooks betrayed any attempt at serious scholarship. They were almost entirely drawings. Even all those advanced psychology courses you needed to graduate (with a degree in psychology) were drawings. On the first page, I’d write down Psyc. I couldn’t even be bothered to write down the entire word — it’d just be Psyc.. or Abnor. Psyc. or Pers. Psyc. and then maybe a course number. After that, perhaps a few notes. And then, less than halfway down the page, it’d start — like some obsessive-compulsive behavior that betrayed my real intent or a nervous tic that had to be satiated.

From that point on, it was all drawings! — which, of course, I couldn’t let anybody see. Because it was bad enough, I wasn’t taking notes and thereby was negligent as a scholar, let alone a college student, and be found out and sent back to grade school (since I somehow wondered how I got beyond it in the first place considering my total failure at concentrating on anything beyond drawings), but then to be drawings Indians besides. I might as well have been drawing Spider-Man, Superman, or Straight Arrow for all the connection it had to deal with reality (which is what psych was all about, wasn’t it? — at least I thought so — that’s why I took it). But Indians! — not even an attempt at reality there. So no, no one ever saw my drawings; in fact, most of my classmates didn’t even know I was an artist until years later when I became “famous” and then the school — yes, the very school that couldn’t wait to get rid of me years earlier — couldn’t wait to give me an honorary doctorate years later!

And yet, ironically, for the very same behavior they wanted me to grow out of years earlier. And yet, ironically, the very same thing that got me attention years later was the very same thing I used to hide years earlier. Except now I was getting paid for the things I was supposed to grow out of — the things that would ruin my life — the things that would doom me to financial failure — for being the child I still was.

And somehow, there is a contradiction here. If I had grown up, I wouldn’t have made the money nor received the praise I now got — but by being what they told me not to be, I ended up becoming what they wanted me to be. And all because of what? I lived out a childhood fantasy. So now, they want that very fantasy I wanted to grow out of. While I don’t? Thus, the final irony — I wanted to do something significant! — like write the 700-page novel that I did! — lambasting the very failure and folly we were both guilty of! — all the while now using those paintings that I considered insignificant — to do what I now considered the most significant — like what we both wanted in the first place!

Can you describe how you aim to make a significant social impact with your book?

I believe in the marketplace of ideas, like George Bernard Shaw, whose dialectical give-and-take plays, like Major Barbara, would take on all sides and let the reader decide. But it’s only through an emotional impact that people are genuinely persuaded — because the pen IS mightier than the sword — mainly if that pen writes a work of fiction with which we can all identify. For example, take Spielberg’s movie Schindler’s List: a black and white movie that used color — once — and only once. The little girl with the red jacket. She’s the one we identify with. Six million Jews were exterminated in the Holocaust — but to most of us, it’s just a statistic. But take one person — the life of one precious child — with whom we can all identify — and suddenly, it becomes real. And that’s the power of Art.

Can you share with us the most interesting story that you shared in your book?

Confessions of St. Augustine, obviously a reference to the original, is a modern-day take on the intellectually hip bad boy for whom nothing is sacred (initially). Like the original, it becomes both a cautionary tale and a manifesto when followed to its logical conclusion. But with one catch: our narrator is unreliable — more prone to comic exaggeration and hyperbole if it gets a laugh.

Ever since I can remember, I have turned pain into comedy. If you were to read an excerpt from my book that would better explain this, it would be the second chapter of the second novel of the trilogy, The Militant. The first chapter starts with what appears to be another story but is merely a story the father is making up for his daughter based on his more recent paintings. But at the end of that short chapter, the main story begins because the second chapter is a 9:00 to 5:00 story, A Day in the Life of the Artist, where our narrator faces every artist’s biggest challenge: the empty canvas.

So if you want to draw parallels (no pun intended), the more the pain, the more the comedy, until in his case, the comedy in the second chapter reaches a fever pitch as his mind wanders over EVERYTHING but what it should: the empty canvas in front of him as he starts out talking to you the reader, then himself, then his ex-wife (in his mind), then his neighbor down the hall who’s constantly pounding on his door when her husband “Crazy Eddy” is away — the local hit man or so he imagines — as does his mind — in this day-long interior monologue talking to everybody, you the reader, himself, his ex-wife, his neighbor down the hall who’s always coming on to him, and everybody else in his life that comes between him and that canvas — and eventually GOD — in desperation. So if it’s all reminiscent of some stand-up comedian’s routine or the plot line of some Walter Mitty-like character out of a 40’s screwball comedy — it’s not by accident. Nor is the parallel behind it.

What was the “aha moment” or series of events that made you decide to bring your message to the greater world? Can you share a story about that?

A year after I had been trained in the Army for no other purpose than to kill — ironically, instead of sending me to Vietnam like most of my friends, half of whom were killed — they sent me to Korea — ultimately to entertain. The month before I left and was on leave, I read Catcher in the Rye. And as I’ve mentioned many times before, that’s the book that changed my life. At that moment, I realized how any voice, spoken in total honesty, can have the influence that that one book had on a whole generation! Not to mention me. From then on, I was determined to write with my voice — which I felt was unique. And THAT’S what motivated me for the rest of my life — to write the Great American novel that would speak to my generation and all the succeeding generations to come, much like Salinger did to his generation.

Without sharing specific names, can you tell us a story about a particular individual who was impacted or helped by your cause?

A New York City-published poet who best represents the reader for whom I wrote the book keeps in constant contact with me and tells me how often, over the years, he has returned to my book again and again for any number of reasons — but perhaps the supreme compliment of all is that he puts my book right up there with James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Are there three things the community/society/politicians can do to help you address the root of the problem you are trying to solve?

Provide the freedom to read whatever a person chooses to read

1- Provide the ability to read whatever they want.

2- Most of all, provide the means to acquire the ability to read it all in the first place.

3- Because it is only through the marketplace of ideas that we can truly learn — PARTICULARLY in the arts — which can reach us on an emotional level in a way that nothing else can — thus being perhaps the most persuasive means of reaching anybody (but that’s just my personal bias).

How do you define “Leadership”? Can you explain what you mean or give an example?

Genghis Khan conquered more land mass than any other conqueror in history — while Jesus, Buddha, Confucius, and Mohamed conquered more minds than anyone in history. He who can conquer the mind is the true leader. All the rest are simply the errand boys — the means to carry out, in many cases, a message even they need help understanding — or they wouldn’t be carrying it out in a way that belied the message itself.

What are your “5 things I wish someone told me when I first started” and why? Please share a story or example for each.

- I should have majored in English in college instead of spinning my wheels and majoring in everything else but English. I consider my academic college career a waste. It was in grad school that I made up for it.

- Listen more to others. For years, my friends said I should read Catcher in the Rye, but I didn’t because they hounded me so much. It wasn’t until years later that I realized what I had been missing: a book that changed my life.

- Take twice as many breaks, and you produce twice as much good work. Once, I was painting a group scene, averaging a person a day until one day, and I spent an entire day just painting one hand. That’s when I realized I needed to take far more breaks

- When you wake up in the middle of the night because something is bothering you, maybe that’s the best time to resolve it — particularly when it comes to creativity — and many other times when you need the perfect solution to a day-long conundrum.

- Reverse your perspective when you hit a wall. For example, when you can only go so far in painting a portrait, take out a mirror and look at it in reverse. Then, it’s like looking at it for the first time.

Can you please give us your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Can you share how that was relevant to you in your life?

“Write the novel you always wanted to read” has been my guiding light for my novel, obviously, and for any other writer of significance worth reading. Ultimately, an artist has no greater judge of his intent and goal than himself.

Is there a person in the world, or in the US with whom you would like to have a private breakfast or lunch with, and why? He or she might just see this, especially if we tag them. 🙂

Martin Scorsese. More than any other director, Martin Scorsese would be the perfect person to film my novel if it ever were offered to a film director. Martin Scorsese was to Francis Ford Coppola what Fyodor Dostoevsky was to Leo Tolstoy. One wrote on a grand scale while the other picked up on the everyday — the spinach in your teeth — comedy that is a part of everyday life — which best represents my book.

How can our readers further follow your work online?

Website: Mueller Art & Literature

Instagram https://www.instagram.com/confessionsofstaugustine/

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/IconoclastPublishingLLC

YouTube https://www.youtube.com/@confessionsofst.augustine4094

Thank you so much for this. This was very inspiring!

Social Impact Authors: How & Why Author James Mueller of Mueller Art & Literature Is Helping To… was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.