…Number one is trust your inner universe, trust where you’re coming from and trust your story, meaning invite your readers to where you are. Don’t try to meet the readers where you think they are.

Number two: write every day and start now. I believe that in order to write the good stuff, you have to write the bad stuff first to get there. So you might as well start today to write the bad stuff…

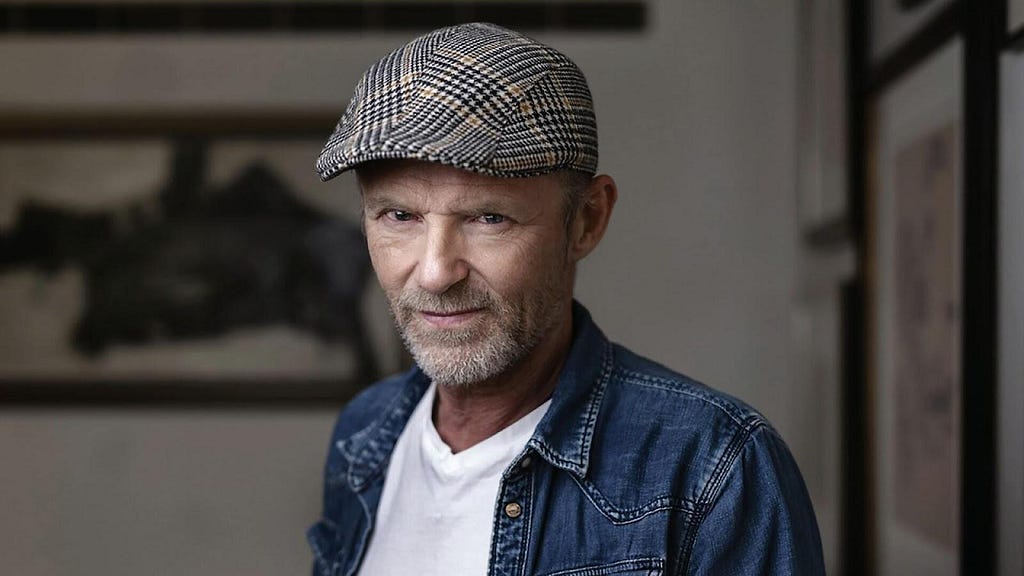

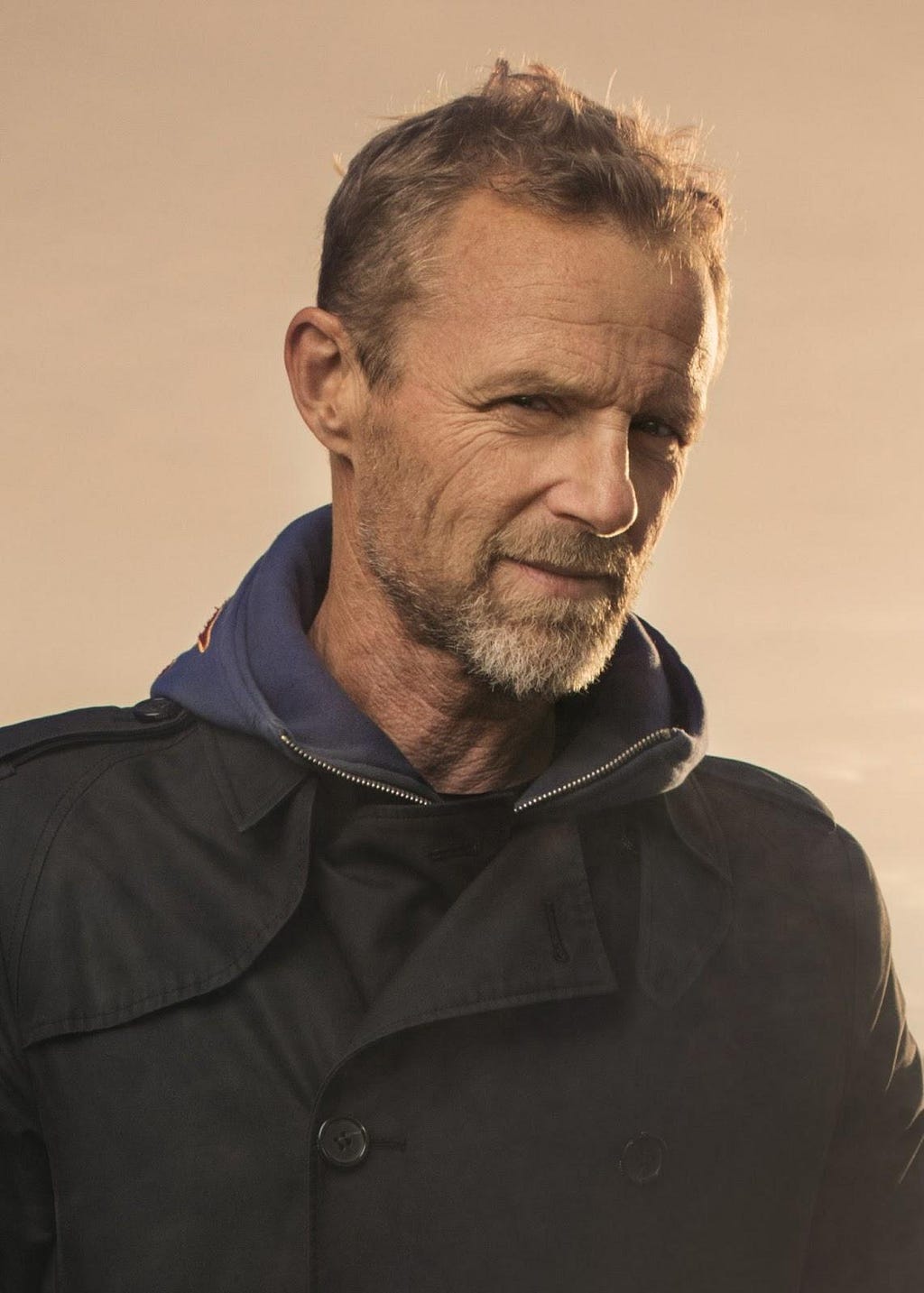

I had the pleasure to talk to #1 New York Times best-selling author Jo Nesbø. Jo, born in Oslo, Norway, stands as one of the most renowned authors in the world, especially celebrated for his expertise in crime novels. Recipient of the Raymond Chandler Award for Lifetime Achievement, as well as many other awards, Nesbø’s books have sold over 55 million copies worldwide, and have been translated into 50 languages — making him the most successful Norwegian author of all time.

Primarily, Nesbø is recognized for his crime novels featuring the character Inspector Harry Hole (“The Redeemer,” “The Snowman,” “The Leopard,” “The Thirst,” “Knife,” and “Killing Moon”). These novels intricately delve into dark themes and criminal investigations, frequently shifting from Norway to various international locations. While the themes of the novels often revolve around perilous situations, they also showcase Hole’s personal challenges, especially his battles with alcoholism.

However, Nesbø’s talents are not limited to crime novels alone. Jo recently released his debut horror novel, “THE NIGHT HOUSE,” showcasing his gifts for immersive settings, memorable characters, and shocking reveals. “THE NIGHT HOUSE” will mesmerize readers of fiction with his twisty, multilayered spin on the coming-of-age horror novel, and is available now.

In 2007, he ventured into children’s literature with “Doktor Proktors Prompepulver” (Doctor Proctor’s Fart Powder), marking the inception of the Doctor Proctor series, which as of 2018, comprises five books. The whimsical series is recognized for its humorous and adventurous themes.

Jo’s repertoire doesn’t end with books. An integral part of the Norwegian rock band Di Derre, Nesbø contributes as the main vocalist and songwriter. Before finding global acclaim as an author, he had diverse experiences, from playing as a striker for the football team Molde FK to working as a freelance journalist and stockbroker.

His multifaceted career also led him to the big screen, with various novels adapted into films. Notable mentions include “The Snowman,” “Headhunters” (based on his novel Hodejegerne), and “The Hanging Sun” (adaptation of Midnight Sun). His talent has also been recognized in the adaptation space with the noir version of Macbeth, set in the 1970s, combining elements of Scandinavia and Scotland.

Outside of his professional life, Nesbø maintains a passion for rock climbing. Starting serious climbing at age 50, by 2023, he achieved a significant milestone by climbing a French grade 8a sport route.

Currently, Jo Nesbø resides in Oslo, where he continues to write, inspire, and climb.

Yitzi: Hello, Jo, it’s a delight and honor to meet you. Before we dive in, our readers would love to learn about your origin story. Can you share with us the story of your childhood and how you grew up?

Jo: I was born in Oslo, and we moved from Oslo to where my grandparents lived on the west coast to a rather small city or town called Molde. That is probably why I always had this romance with Oslo, because it was my happy childhood valley, and I always longed to go back there. It’s almost like a character in the Harry Hole series. Molde was a great place to grow up, but I kept my Oslo dialect while my brothers quickly adapted to the Molde dialect. So maybe I just wanted to be kind of an outsider.

I wasn’t like a real outsider, like in my latest novel, “The Night House” — you have this character Richard, who is definitely an outsider. I was more an outsider by choice, well-adapted but also a sort of recluse of the family. The rest of my family was very social, and whenever my family gathered, I would rather stay in my room while they would socialize. At some point, they would yell at me, “Jo, come on, you have to be together with us too.” But I’d rather be in my room, reading or coming up with stories. And so I never thought about it that way, but actually, I was the recluse of the family, and my family was not only happy to socialize, but also happy to tell stories, and that went for most of my relatives.

So when we gathered for Christmas holidays or other holidays, it would be my uncles, aunts, and my father sharing stories — and it wouldn’t be new, exciting stories. It would be the same stories, but they often were equipped with new endings and surprise twists and turns from the last time we heard them. So they were sort of retelling stories, but still making it up as they went along. I’d say that was my “writer’s school” in many ways. I just listened and probably subconsciously analyzed how they told the stories, and how they made them great, and also when they failed from time to time.

So when we got the kids gathered in the attic and it was time to tell ghost stories after sunset, they would turn to me and say, “Jo, you tell.” So I would tell ghost stories and I was pretty proud. I thought it was great that they must have thought I was a great storyteller because they would always turn to me, being the youngest and all. It was until years later when they told me that they wanted me to tell the stories because when I told them, they could hear the fear in my voice. And it was true. I was always very much into my stories. I would scare not only the kids, but I would scare myself.

I have to mention the essay we had in school. You probably had that too when the teacher would give you the title for the essay and it would be something like “a nice day in the woods” and you’re supposed to write two pages or so. But I would write more like 12 pages. In my version of a nice day in the woods, nobody would come back alive. So my mother told me she got a call from a worried teacher wondering “what’s going on with Jo?”

Most of my childhood was spent playing soccer. It was me and my younger brother; we played soccer and after some years, at quite a high level. If you asked a 15-year-old me what I’d do for a living, my answer would likely be that realistically, “I think I’m going to play professional football.” Maybe for a Norwegian team, but hopefully, I’ll play for Tottenham in London. That was the dream. I even played my first match for Molde, a town where everybody plays soccer. Despite having a population of only 15,000 at that time, Molde was in the Norwegian Premier League and also played in the Champions League and Europa League. It’s an amazingly good football club for a small town. But then, at 19, I tore the ligaments in both my knees, so I had to come up with Plan B. With no clear idea of what I wanted to do next, I decided to study economics.

I then went to Bergen for my studies and pursued a master’s in economics, but around that time, I also started playing in a band. When I was younger, most of my friends played in bands. I didn’t play myself, but I would write the lyrics for my friends’ bands. So as a student, we started a band, and I began writing music too, learning to play the guitar.

When I started working as a financial analyst in Oslo, my friends from Molde, including my brother, and I formed a band. We played in a small club in Oslo. Nobody took us seriously, and we didn’t take ourselves seriously either. We were so awful that sometimes the audience would beg us to stop playing so they could talk. It got to the point where we changed the name of the band for every gig so that people would come back thinking it was a different group. Eventually, we got better. People started asking if “those guys” were going to play next weekend. That became the name of the band — Those Guys — but in Norwegian. Out of the blue, we had a local hit that caught the attention of some record companies, leading to a record deal. We were unsure about taking it, but we went for it, recorded an album, and although it didn’t sell much, our second album had two great hits.

Suddenly, we were the best-selling band in Norway. It came out of nowhere, and we weren’t prepared for it, but it was great fun. By then, the rest of the band were full-time musicians, and while I was a singer and a songwriter, I insisted on keeping my day job because I didn’t see myself as a musician. I saw myself as a creator of stories. The popularity of the band probably had more to do with the lyrics than the music. Juggling my day job and doing more than 100 gigs a year, I was pretty much burned out. So, I told my band and my boss at the brokerage firm that I needed a long break. I planned to go to Australia. Around the same time, a girl I knew from my student days approached me. She liked my lyrics and was working for a publishing house. She asked if I could write a book about the band. I declined, citing the golden rule of bands — what happens on the road stays on the road — but offered to write something else. I had been contemplating writing a novel for a while. On the plane to Australia, I came up with this character, Harry Hole. I had a vague idea of a plot. During the five weeks in Australia, I spent more time writing about Harry Hole than exploring the country. Where I went, Harry would go. When I returned, I realized I had fallen in love with writing. I knew this was what I wanted to do. It was something I loved more than touring with the band or my job as a financial analyst.

So when I came back, I went to my boss’ office and said that I had a great time here and thanked him profusely. But there were other things I needed to do. My father had died three years earlier, just as he had retired. That was when he was going to write his book about his experiences during World War II. But he died that same year from cancer. The lesson I took from that was that you can’t really postpone the things you need to do in life. So I told my boss, I need to quit. I had made enough money here so I wouldn’t have to worry about finances for the next five years. I could live a simple life and get by. And that was my plan, five years of being a pro writer. That was how I envisioned my future.

Then three weeks after I quit my job, the girl from the publishing house called me and said that she showed the script I sent her to her bosses in the fiction department, and they loved it and wanted to publish it. Suddenly, I transitioned from being an out-of-work economist to being a writer. Of course, my first book didn’t sell much, but it received very good reviews and a couple of prestigious prizes. However, it wasn’t enough for me to make a living as a writer. But then with my second novel, the second in the series about Harry HOLE, which was probably my weakest novel, it did okay because of the following the first novel had gained.

It wasn’t really until my third novel, “The Redbreast,” that things changed. In that novel, I told the story my father had planned to share about his experiences in the trenches outside Leningrad during World War II. He and I had spent hours discussing his experiences and all the craziness that went on there, and that became the material I used in “The Redbreast.” That was both my commercial and, in every other way, my breakthrough as a writer. Suddenly, I was a best-selling author and received the Booksellers’ Prize for that year, which is probably the most prestigious prize in Norway. That’s when I knew that I could probably make it as a full-time writer.

Yitzi: It’s clear that you’re an amazing storyteller; the way you told that story is amazing. You probably have so many interesting experiences from your very diverse and varied career. Can you share with our readers one or two of your favorite stories or favorite memories?

Jo: One of the things I like about being a writer is the sense of anonymity it can provide. They say that writers are “shy exhibitionists”, and I think I fall a bit into that category. I don’t mind being on stage for something worthwhile, but I appreciate the idea of walking into a bookstore, where no one knows who you are, yet you can see your books on the shelf. I love that my work is on display, but I’m not. However, there’s a limit to that anonymity. A little recognition is nice.

I recall this one time in Manila, Philippines, early in my career. I went into a bookstore to buy some books, and I noticed they had “The Redbreast” on a shelf behind the counter. It was astounding to see my book all the way in Manila! I was there with my stack of books to buy, and I just had to tell the woman behind the counter that I wrote the book displayed there. She said she’d get the boss, and before I could say anything, she was gone. There was a queue forming behind me, and it was somewhat embarrassing as everyone was wondering what the fuss was about. She returned with her boss, who asked if I was indeed the author of that book. I knew there was a picture of me on the book, but it was wrapped in plastic, and they couldn’t open it as they wouldn’t be able to sell it afterward. She asked for an ID, but I had left my passport at the hotel. She then mentioned that without an ID, she couldn’t give me a writer’s discount on the books I was buying. I clarified that I wasn’t looking for a discount; I thought maybe they’d like some signed copies. After discussing with a colleague, she said if I came back with my passport the next day, I could sign two books.

As I was leaving, I could sense the irritation from the queue, and I overheard an old lady behind me, looking at the book and reading my name “Jo “ with a J.O., commenting to her friend, “Isn’t that a girl’s name?” It’s good to remain unnoticed at times, but a little respect now and then would be appreciated.

Yitzi: So this is the main part of our interview. You have a lot of experience now. You’ve been blessed with a lot of success for an up-and-coming writer, for an aspiring young writer. Can you share a few things that you need to be a highly successful writer?

Jo: First of all, I want to clarify that I may not have all the answers. I say that because, well, the following suggestions might not be the definitive steps to success. These are just a few ideas that may help, though I might be very wrong about them. Just wanted to put that out there before we dive in.

Okay, number one is trust your inner universe, trust where you’re coming from and trust your story, meaning invite your readers to where you are. Don’t try to meet the readers where you think they are.

Number two: write every day and start now. I believe that in order to write the good stuff, you have to write the bad stuff first to get there. So you might as well start today to write the bad stuff.

Number three: I only have two. (Laughs)

Yitzi: Okay, this is our aspirational question. So Jo, because of the platform that you’ve built and your great work, you’re a person of enormous influence and people take your words seriously. If you could spread an idea or inspire a movement that would bring the most amount of good to the most amount of people, what would that be? Because you never know what your idea can inspire.

Jo: First of all, an introduction here too. It’s an attitude towards writers which stems from 200 years back or more. When writers were a class that would not have to do hard labor, they could stay at home while the real providers were out there working in the fields or doing whatever they needed to put food on the table for the families. Then they would expect writers to have stayed at home and done some serious thinking. So they could come back and read what they had written and become wiser. That is no longer the case. But still, the world is turning to people who make a living just making stuff up while they themselves are studying real science in universities. But still, they are asking writers about life and how to exist as human beings. I’m really thankful for that. I feel privileged that we are misunderstood in that sense. Having said that, I’m going now to deliver my words of wisdom. It’s quite a simple thing. There is no such thing as universal and eternal morality. Morality is not heaven-sent, but society’s traffic rules to survive and thrive. Different societies have different needs and therefore different traffic rules. These practical and useful rules do, however over time, become so internalized that it may feel as if we were born with them. And certainly, Jonathan Haidt in “The Righteous Mind” refers to research that suggests that we are born with some basic “moral instincts,” however, when we see societies obeying different traffic rules and feel that moral indignation swell up in us, and it feels that our God-given moral compass is telling us something that is true for every human being, it’s maybe time to reflect on what the great philosopher Dave Hume said: reasoning is the slave of emotions. In “A Political History of the World” Jonathan Holslag concludes there is no moral higher ground in the societies and nations wars over the last 3.000 years.

Yitzi: It’s a great point. Basically, what you’re saying is that we have to have the humility that we’re not better than anybody. We’re not better.

Jo: All groups take care of their interests. Indeed, being a deserter is being looked down upon even when the deserter joins our side of the moral divide. Heir side. And here’s another point made by Jonathan Haidt, who studied behavioral psychology and social anthropology, the selfish mind is focused on taking care of number one. But to an even larger extent than we have believed up until now, individuals are also taking care of their group. And here’s an interesting statistic — though it may not be directly related to this interview — an interesting point he makes is when you look at how people vote, for example, in the United States, you may ask the question, why do people who do not benefit from Donald Trump’s policy vote for Donald Trump? I mean, workers, and people without health insurance, how come they vote for Trump when it would serve their life situation better to vote Democrat? It’s because people vote for their group, vote for who they feel are speaking for them, defending their group more than themselves individually.

Yitzi: How can our readers continue to follow your work? How can they purchase your books? How can they purchase your music? How can we just continue to support you in any way? How can our readers learn more about you and purchase your content?

Jo: I don’t know. My publisher is going to kill me for saying this, and I probably should know, but I don’t. (Laughs) They can go to their local bookstore. They can probably buy it on the internet. And yeah, if you need to buy it on the internet, that’s fine, but ideally, if there’s still a bookseller alive close to where you live, go there and support the bookstore.

Best-Selling Author Jo Nesbø On What It Takes To Become A Highly Successful Author or Writer was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.